Linear Arithmetic (LA) Synthesis revolutionized digital music production by bridging the gap between realistic sampling and creative synthesis flexibility. This groundbreaking hybrid approach, introduced by Roland Corporation in 1987 with their legendary D-50 synthesizer, solved a critical problem facing musicians of the era: how to achieve the authentic sound of expensive samplers while maintaining the programmability and creative control of traditional synthesizers. The innovation combined short PCM samples of instrument attacks with subtractive synthesis for sustained portions, creating sounds that were both realistic and musically expressive.

LA Synthesis fundamentally changed how producers approached sound design, offering a psychoacoustically-informed solution that recognized how human hearing processes musical sounds. By focusing processing power on the attack transient—the portion of a sound most crucial for instrument recognition—while using efficient digital synthesis for sustain portions, Roland created a synthesis method that delivered maximum impact with minimal memory requirements. This approach became the foundation for modern sample-based synthesis and influenced synthesizer design for decades to come.

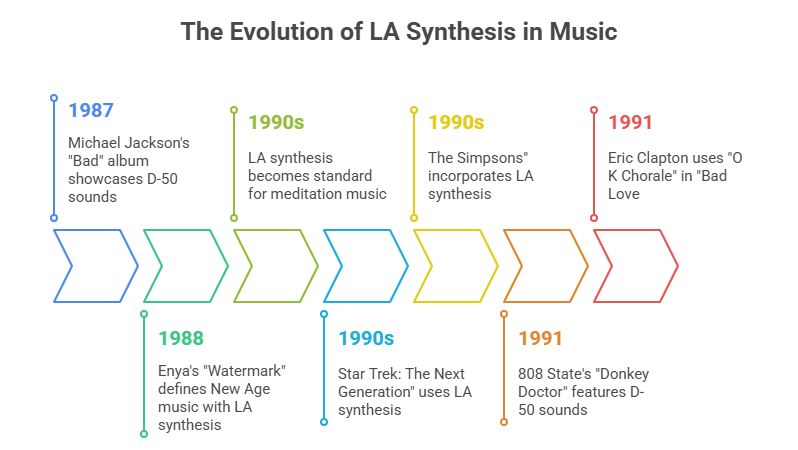

The cultural impact was immediate and lasting. LA Synthesis powered hit records across multiple genres throughout the late 1980s and 1990s, from Enya’s ethereal “Orinoco Flow” to Michael Jackson’s “Bad” album. The distinctive character of LA synthesis—warm yet precise, realistic yet otherworldly—defined the sound of an era and continues to inspire producers seeking authentic vintage character in modern productions.

How LA synthesis creates its distinctive sounds

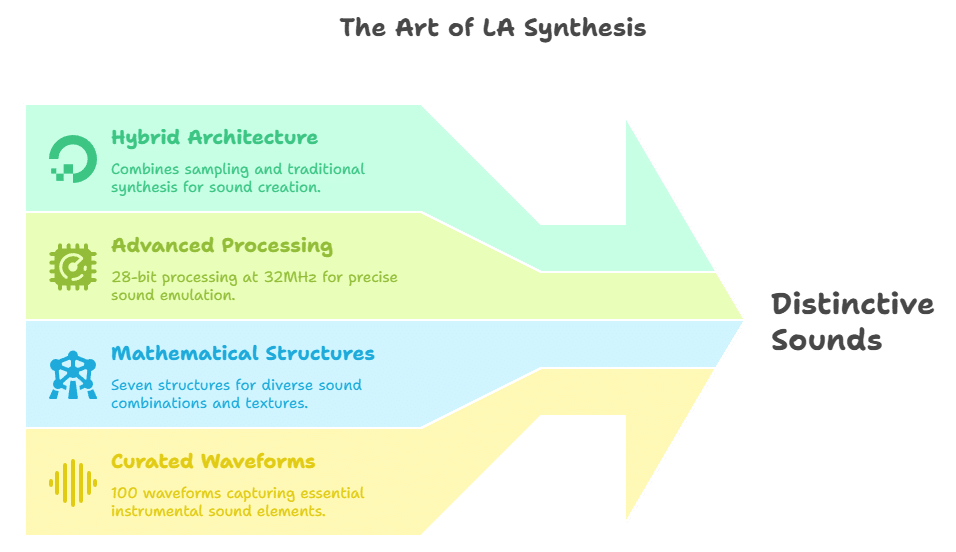

The magic of LA Synthesis lies in its intelligent approach to sound construction. Unlike purely analog or digital synthesis methods, LA synthesis employs a hybrid architecture that combines the best aspects of sampling and traditional synthesis. The system organizes sound generation into a hierarchical structure: individual sound generators called “partials” form the foundation, which combine into “tones,” and finally merge into complete “patches.”

Each partial functions as a complete synthesizer voice, capable of either PCM sample playback or traditional digital oscillator generation. The Roland D-50’s custom DSP architecture featured remarkable specifications for its time: 28-bit internal resolution processing at 32MHz, far exceeding the 12-bit samplers that dominated the market. This processing power enabled sophisticated digital filtering and modulation that closely emulated analog synthesizer behavior while maintaining the precision of digital technology.

The system’s seven different “structures” determine how partials combine mathematically. Simple linear addition creates lush pads and orchestral sections, while ring modulation between partials generates complex, digital-flavored timbres impossible to achieve with analog synthesis alone. This flexibility allows sound designers to create everything from realistic brass sections to otherworldly atmospheric textures using the same underlying architecture.

The PCM sample library consists of 100 carefully curated waveforms: 47 attack transients capturing the signature onsets of brass, strings, and percussion instruments; 29 static loops for sustained textures; and 24 composite loops containing rhythmic sequences and complex harmonic content. This focused approach to sampling prioritizes the most perceptually important aspects of instrumental sounds while maintaining creative flexibility for sound design applications.

Roland’s revolutionary engineering breakthrough in 1987

LA Synthesis emerged from Roland Corporation’s response to market pressure from Yamaha’s hugely successful DX7 FM synthesizer. While FM synthesis excelled at metallic and percussive sounds, it struggled with warm, organic textures that defined traditional music production. Roland engineers, led by the development team at their Los Angeles facility, recognized that the most challenging aspect of realistic synthesis was reproducing authentic attack transients—the initial few milliseconds that primarily determine how listeners identify musical instruments.

Eric Persing, Roland’s Chief Sound Designer from 1984-2004, played a pivotal role in defining LA synthesis through his legendary preset programming. Working alongside Adrian Scott and the R&D team including Chris Meyer, Mark Tsuruta, and Bob Daspit, Persing created iconic sounds like “Fantasia,” “Soundtrack,” “Digital Native Dance,” and “Pizzagogo” that became synonymous with 1980s music production. These factory presets demonstrated LA synthesis capabilities so effectively that many were later incorporated into the General MIDI specification.

The technical innovation centered on Roland’s custom Fujitsu gate array DSP, containing 10,000-20,000 logic gates and operating at frequencies that pushed the boundaries of 1987 technology. This dedicated processing power enabled real-time digital filtering with 4-pole topology, sophisticated envelope generation with five-stage precision, and three LFOs per partial for complex modulation possibilities. The engineering team’s achievement was creating a system that felt familiar to synthesizer players while delivering unprecedented sonic realism.

Roland’s marketing positioned the D-50 perfectly, earning a TEC Award for outstanding technical achievement in 1988 and achieving commercial success that established the company as a digital synthesis leader. The timing coincided with the rise of music sampling lawsuits, making LA synthesis an attractive alternative for producers seeking realistic sounds without copyright complications.

Musical applications across genres and decades

LA Synthesis found immediate adoption across diverse musical styles, proving its versatility beyond the new age and ambient genres where it seemed naturally suited. Pop and R&B productions embraced the technology extensively, with Michael Jackson’s “Bad” album serving as a showcase for D-50 sounds throughout tracks like “Man in the Mirror,” “Dirty Diana,” and “Liberian Girl.” The synthesis method’s ability to create both rhythmic percussive elements and lush atmospheric pads made it invaluable for pop arrangements.

New Age music became synonymous with LA synthesis character, particularly through Enya’s breakthrough album “Watermark.” The famous “Pizzagogo” preset provided the distinctive pizzicato string sound that defined “Orinoco Flow,” while the D-50’s atmospheric pads created the spiritual, otherworldly textures that characterized the genre. This association was so strong that LA synthesis became the de facto standard for meditation and relaxation music throughout the 1990s.

Film and television scoring adopted LA synthesis for its ability to create cinematic soundscapes efficiently. The technology appeared in soundtracks for “Star Trek: The Next Generation,” providing futuristic atmospheric elements, and “The Simpsons,” contributing to the show’s musical palette. Composers appreciated how LA synthesis could suggest orchestral sections without requiring actual orchestral recordings, making it particularly valuable for lower-budget productions seeking professional polish.

The method’s influence extended to electronic dance music, where artists like 808 State incorporated D-50 sounds into tracks like “Donkey Doctor.” The synthesis method’s digital precision and complex harmonic content provided textural elements that complemented the emerging acid house and techno movements. Even rock productions utilized LA synthesis, with artists like Eric Clapton featuring the “O K Chorale” preset prominently in “Bad Love.”

Comparing LA synthesis with contemporary synthesis methods

LA Synthesis occupies a unique position in the synthesis landscape, offering advantages and limitations that distinguish it from other approaches. Compared to subtractive synthesis, LA provides significantly more realistic instrumental emulations through its PCM attack samples, while maintaining familiar analog-style programming concepts. However, the added complexity of partial management and structure selection creates a steeper learning curve than straightforward analog synthesis.

Against FM synthesis, LA synthesis offers more intuitive programming and warmer, more organic sound character. Where FM excels at metallic and percussive textures through its cross-modulation algorithms, LA synthesis shines with realistic brass, strings, and atmospheric pads. The linear nature of LA synthesis makes it more predictable than FM’s non-linear behavior, appealing to producers who found DX7 programming cryptic and challenging.

Wavetable synthesis shares LA synthesis’s focus on combining multiple sound sources, but with different strengths. While wavetable synthesis excels at morphing between different timbres within sustained notes, LA synthesis provides superior attack transient realism through its sampled components. Modern wavetable synthesizers often incorporate LA-style approaches, using samples as wavetable sources to combine the benefits of both methods.

Pure sampling offers greater realism than LA synthesis but requires significantly more memory and lacks creative flexibility. LA synthesis achieves approximately 80% of sampling’s realism using roughly 20% of the memory, while providing synthesis parameters for sound modification impossible with static samples. This efficiency made LA synthesis the preferred choice for mid-range keyboards throughout the 1990s.

Technical advantages for modern producers

The enduring appeal of LA synthesis stems from several technical advantages that remain relevant in contemporary production environments. Memory efficiency continues to benefit modern software implementations, allowing complex sounds with rich harmonic content while maintaining reasonable CPU usage. The hybrid approach enables sounds that would require multiple plugins or samples in traditional production setups.

Velocity and aftertouch integration in LA synthesis provides exceptional expressive control. Every synthesis parameter can respond to performance dynamics, creating sounds that feel alive and responsive under playing. This comprehensive modulation system predated modern synthesizer standards and remains sophisticated by contemporary measures. The five-stage envelope generators offer more detailed control than standard ADSR envelopes, enabling precise articulation shaping.

Built-in effects processing was revolutionary for 1987 and remains convenient today. The integrated digital reverb, chorus, and delay algorithms were specifically optimized for LA synthesis sounds, providing polished results without external processing. Modern software implementations often enhance these effects while maintaining the characteristic LA synthesis processing chain that contributes to the method’s distinctive sound.

Real-time modulation capabilities through the three LFOs per partial create complex evolving textures that would require extensive automation in conventional synthesis approaches. The modulation routing flexibility allows subtle parameter variations that keep sounds interesting throughout extended passages, particularly valuable for atmospheric and ambient applications.

Current software and hardware options

Modern producers have several paths to access authentic LA synthesis sounds and capabilities. Roland Cloud’s D-50 software synthesizer represents the most faithful recreation, using Digital Circuit Behavior modeling to replicate the original hardware’s DSP algorithms precisely. The subscription-based service includes all original presets plus expansion card sounds, with a virtual PG-1000 programmer interface that makes deep editing far more accessible than the original hardware.

Roland’s D-05 Boutique provides authentic LA synthesis in compact hardware form, incorporating all expansion sounds and adding modern conveniences like USB connectivity and pattern sequencing. While the small form factor limits hands-on control, the sound engine remains faithful to the original D-50 architecture. The unit serves as both a performance instrument and desktop sound module for modern studio setups.

Vintage Roland hardware remains available through used markets, with D-50 and D-550 units commanding $400-1200 depending on condition. Original hardware provides the complete authentic experience, including the characteristic analog output circuitry that contributes to the D-50’s warmth. However, vintage units require maintenance consideration and benefit significantly from the PG-1000 programmer accessory for practical sound editing.

Third-party software options include various developers creating LA-style synthesis engines, though none match Roland’s official implementations for authenticity. Some modern synthesizers incorporate LA synthesis principles, particularly in workstation keyboards where sample+synthesis approaches dominate. The concepts behind LA synthesis influence many contemporary instruments, even when not explicitly labeled as such.

Programming techniques and creative applications

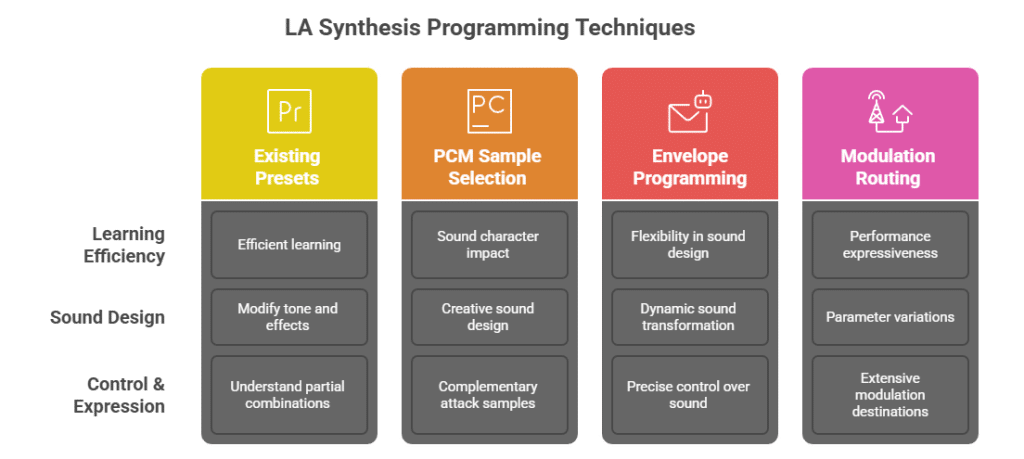

Effective LA synthesis programming requires understanding the hierarchical architecture and leveraging the interaction between PCM samples and synthesized elements. Starting with existing presets provides the most efficient learning approach, allowing producers to understand how different partial combinations create complex sounds before attempting original programming. Modifying tone balance and effects settings offers immediate results while building familiarity with the system.

PCM sample selection critically impacts the final sound character. Attack samples work best when they complement rather than conflict with the sustain synthesis elements. Creative sound design emerges from combining unexpected attack types with contrasting sustained sounds—orchestral attacks with synthesized bass timbres, or percussive samples with ambient pad textures. This approach generates unique sounds impossible to achieve with conventional synthesis methods.

Envelope programming in LA synthesis uses five-stage contours offering more flexibility than standard ADSR shapes. The graphical envelope display in modern software implementations makes this complexity manageable, enabling precise control over attack, decay, sustain, and release characteristics. Effective envelope programming can transform static PCM samples into expressive, dynamic sounds that respond naturally to performance nuances.

Modulation routing through LFO assignments and velocity/aftertouch mapping creates the performance expressiveness that distinguishes musical instruments from static sound effects. LA synthesis provides extensive modulation destinations, allowing subtle parameter variations that maintain listener interest throughout sustained passages. Modern productions often automate these parameters through DAW controllers, creating evolving textures that enhance musical arrangements.

Conclusion: LA synthesis in contemporary music production

LA Synthesis represents a pivotal moment in electronic music history, successfully bridging analog warmth with digital precision while solving practical problems of cost, memory, and creative control. Its influence extends far beyond the Roland D-50, establishing sample+synthesis as the dominant approach for modern workstation keyboards and software instruments. The method’s emphasis on attack transient realism combined with synthesis flexibility created a template that continues to guide contemporary instrument design.

For today’s producers, LA synthesis offers distinctive vintage character that cannot be replicated through other synthesis methods. The sounds carry emotional resonance tied to classic hit records while providing creative possibilities for modern applications. Whether creating authentic 1980s nostalgia, atmospheric film scores, or layered electronic textures, LA synthesis provides efficient access to professional-quality sounds with immediate musical impact.

The technical innovations pioneered in LA synthesis—psychoacoustic optimization, hybrid architecture, and comprehensive performance control—remain relevant in an era of unlimited processing power and memory. Sometimes the most effective approach combines proven techniques with modern implementation, making LA synthesis as valuable today as when it first revolutionized digital music production nearly four decades ago.

Back to Music Production Terms Index Page